“This above all: to thine own self be true

And it must follow, as the night the day

Thou canst not then be false to any man…”

– William Shakespeare

Shakespeare’s quote from Hamlet, “This above all: to thine own self be true,” teaches that a person must remain faithful to their inner beliefs as Dr. Ida Scudder did.

Early Life and Background

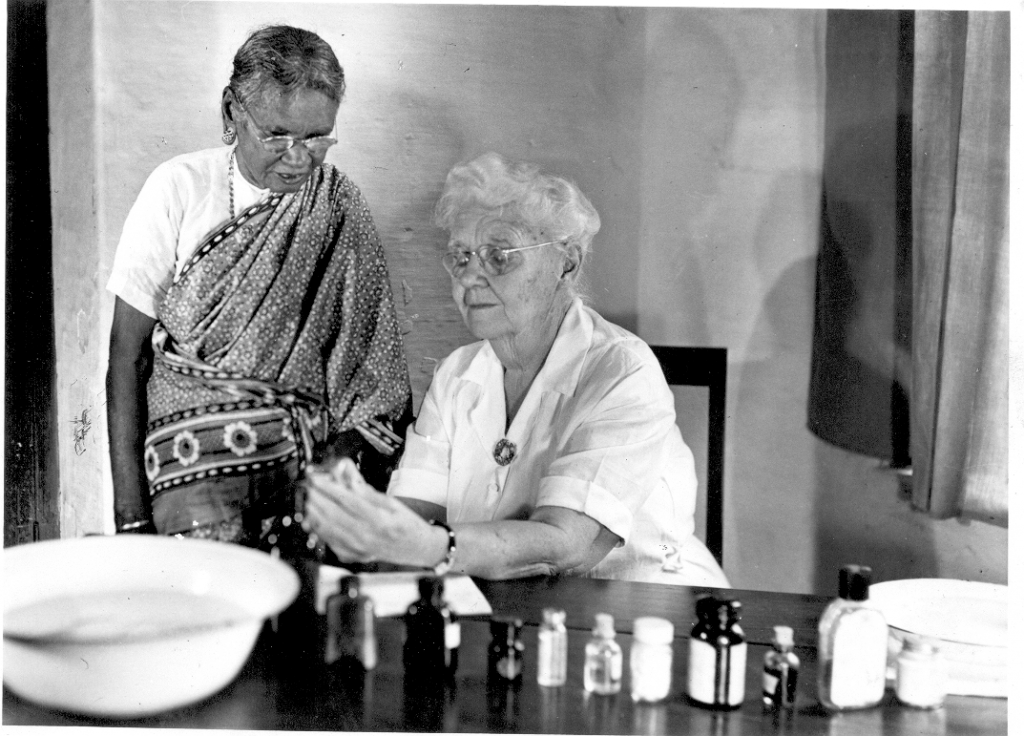

Born in South India in 1870, Ida Scudder, the founder of CMC Vellore, spent most of her childhood in the US and was educated there.

Although her grandparents, Ida’s grandfather, Rev. John Scudder (left) and his wife, Harriet Waterbury Scudder were the first of the Scudders to arrive in India as medical missionaries, her parents and most other members of her extended family had served as missionaries in India – this was not the life that she wanted.

However, one night, while visiting her parents at their home in India, her life was turned around.

The Turning Point

Three well-to-do men came to the house one after the other, with the same desperate story. Each of them had a young wife in the throes of childbirth, but unable to deliver. The traditional midwife had been unable to help. Would the young mistress come and help deliver the baby?

Ida had no medical training at that point, and suggested that her doctor-father should go. However, owing to the social and religious customs of the day, each of these men went away sadly, saying that it was impossible for another man to see their wives. With no doctor to look after them, these three women and their babies all died that night.

Ida took this as a clear signal from God that she should strive to help the women and children of India. (Read the story of ‘The Three Knocks’ in Ida’s own words below)

The Three Knocks: Dr. Ida Narrates

The First Knock

As I sat alone at my desk, in my room in the little bungalow, I heard steps coming up to the verandah and looking up I saw a very tall and fine-looking Brahmin gentleman.

I asked him what I could do for him, and he said his little wife, a mere child, was in labour and having a very difficult time and the untrained Barbers’ wives had said that they could do nothing for her, and asked if I could go and help her.

I told him that I knew absolutely nothing about midwifery cases but that my father was a Doctor and that when he returned from a call he would gladly come and help. The man drew himself up and said,

“Your father come into my caste home and take care of my wife! She had better die than have anything like that happen.”

Later, I took him over to my father’s study and together we pleaded with him and I told him that I would do everything in my power to help his wife, with my father, if he would only let us come! I would be an assistant! Still, he refused. Father also urged him, but he went away, apparently very unhappy because I could not help.

The Second Knock

I went to my desk very much stirred by that first encounter. After a time I heard steps again on the verandah and jumped up, hoping that the man had returned to take my father and me, but instead of seeing the Brahmin gentleman, I saw a Mohammedan who had come to see me, and I was horrified to hear the same plea from him. His wife was dying, a mere child, and would I come and help?

Again, I said I knew nothing about midwifery cases. I took him to my father, and we both reasoned with him, and I said that I would go with my father who was a Doctor, and do what I could to help. A scornful answer made my heart sad. He utterly refused saying that no one outside his family had ever looked upon the face of his wife.

‘She had better die than have a man come into the house,’ he said. Again my father and I urged him to allow us to come, but again he refused repeating that she had better die than have a strange man look upon her face; and he left.

The Third Knock

I went back to my room with my heart so burdened that I hardly knew how to overcome it. After some time of thinking and trying to get my mind back onto my book, I again heard footsteps, and, running to the door, looked out to see if the second man had come back, but again I was more than horrified to have the same plea coming from a third man, a high-caste Hindu. He refused just as the others had done, and vanished in the darkness.

A Night of Decision

I could not sleep that night – it was too terrible. Within the touch of my hand were three girls dying because there was no woman to help them. I spent much of the night in anguish and prayer. I did not want to spend my life in India. My friends were begging me to return to the joyous opportunities of a young girl in America, and I somehow felt that I could not give that up. I went to bed in the early morning after praying much for guidance. I think that was the first time I ever met God face to face, and all that time it seemed that He was calling me into this work.

The Morning After

Early in the morning I heard the ‘tom-tom’ beating in the village and it struck terror in my heart, for it was a death message. I sent our Servant, who had come up early, to the village to find out the fate of these three women, and he came back saying that all of them had died during the night. As a funeral passed our house during the morning, it made me very unhappy. I could not bear to think of these young girls as dead.

Again I shut myself in my room and thought very seriously about the condition of the Indian women and after much thought and prayer, I went to my father and mother and told them that I must go home and study Medicine, and come back to India to help such women.

This account is taken from the book ‘Ida S. Scudder’ by Pauline Jeffrey.

Medical Education and Return to India

She returned to the US to study as a doctor, graduating from Cornell University Medical College in 1899, among the first batch of women. She started her medical work in Vellore in 1900, using one room in her parents’ bungalow as a one-bedded clinic-cum-dispensary. (In 2025, we celebrated 125 years since the starting of that single-bedded clinic) which marks a milestone.

In view of her earlier experience, her focus was on women and children; at that time there were hardly any women doctors in India. Gradually her reputation grew and with it, the demand for her services.

Growth of the Hospital

In 1902, she opened the 40-bedded Mary Taber Schell Memorial Hospital, built using funds donated in the USA.

In 1924, a new 267-bedded hospital was opened in the centre of Vellore, which has continued to expand there ever since. In 2025, we celebrated 125 years since the starting of that single-bedded clinic.

Vision for Training and Education

Ida knew she could have little impact working on her own, and her vision was not just to treat, but also to train others. So she began teaching ‘compounders’ – modern day pharmacists – and nurses.

Last updated on 19 February, 2026.

Watch a video depicting the story below: